I've been playing, and enjoying, videogames obsessively for 18 years now, so you may say I'm biased, or overly optimistic in declaring them a stronger medium than movies or novels, and, admittedly there is still a stigma and a raft of misconceptions surrounding videogames. There is also, more than many other mediums, a couple of barriers to entry: firstly the requirement of often expensive, specialist, hardware to experience them, and secondly the inherent challenges within a game which make it a game. A novel is inexpensive, and a film does not prevent your progression by testing your mastery of concepts presented within it.

I'll answer the problems, or weaknesses, of videogames first, before I explain why I think it is such a strong medium (hint: videogames essentially combine the best traits of many other mediums).

The first barrier to entry, that of the requirement for expensive hardware, is similar to my criticism of stage-plays, which can often have expensive ticket prices for relatively short experiences. However, while current consoles cost in the hundreds, and new games generally carry £40 to £50 price tags, many worthwhile games can be played for free, or for very little cost, on computers and devices which you already own.

Take Passage for example (http://hcsoftware.sourceforge.net/passage/), a short but sweet game which comments on the nature of life and the passage of time without saying a word. Chances are you own a computer running either Windows, Mac OS, or Linux, and if you do, you can play the above game for free right now.

|

| The primitive aesthetic of Jason Rohrer's 'Passage' belies its emotional impact. If you own a computer, you can experience it for yourself right now. |

Also, consider this: a ticket for a professionally-produced stage-play might cost, on average, around £20. Say the play lasts roughly 2 hours, that £10 per hour of entertainment. A new DVD may cost upwards of £10, again for 2, or even 1.5 hours of entertainment, making it £5 per hour. The shortest full-price retail games will last more than 8 hours, depending on the genre, and many will last longer. At 8 hours' entertainment for £40, that's £5 per hour. I've bought £5 games before which have lasted me 50 hours. That's £0.10 per hour of entertainment (excluding the initial cost of the console).

I would argue therefore that the cost of entry is not as unreasonable as it first appears when traded off against the potential returns.

The second barrier to entry I raised is the challenge, or perceived challenge, of videogames. Some videogames are unapologetically challenging. This is part of their appeal. Many older videogames, particularly those made pre-c.1996* require dedication and high levels of skill to finish. However, whether a game is challenging or not is an individual design decision, not an inherent aspect of a videogame. The videogame I linked to above, Passage, is not challenging in the slightest, at least in so far as there is no fail-state: you cannot lose at the videogame, you can only experience it.

(Arguably therefore, with no win/lose-state, Passage is not a 'game' at all. For my purposes in this post, 'game' and 'videogame' are not the same thing. A 'game' I would define as a challenge for one of more players to reach one, or one of several, predefined, conclusion(s) by following a set of previously defined abstract rules. I say 'abstract' rules because there may be ways to 'cheat' the game by exploiting the physical properties of the game pieces or equipment outside of these rules. For example, in chess, one could physically move a bishop along a vertical or horizontal plane, but this would contravene the abstract rule that bishops can only move diagonally. An example of a 'game' would be chess or, more improvisationally, something as simple as a person with a rubber ball challenging themselves to bounce it off a wall and into a bucket. (The abstract rule "I must rebound the ball from the wall into the bucket to win" makes this a game).

A videogame I would define, firstly, as an interactive experience created through electronic means within which a series of predefined physical inputs from the user result in specific actions within the interactive experience (eg. pressing 'A' makes a character jump). So far this definition could apply to productivity software or an internet browser, so a further stipulation is required. I would add, secondly, that videogame, like a game, must also have either a win/lose state or, not necessarily like a game, seek specifically to evoke an emotional, critical, or philosophical, response from a player or, alternatively, to tell some sort of narrative (which is more or less the same thing as seeking to evoke a response).)

Many videogames now offer different levels of challenge to cater for a variety of player preferences. For example, you may have easy modes which give player-avatars increased resistance to damage, such as in Call of Duty; optional driving assists which make cars less likely to spin out, such as in Forza; instructional videos on how to complete challenges, such as in recent Mario and Zelda games; and even occasionally spectator modes, where the game will automatically complete sections of game if the player finds it too challenging (I believe one of the New Super Mario Bros. or possibly one of the Kirby titles had this feature).

|

| The original 'Doom' has some memorable difficulty level names |

So, as I previously mentioned, challenge is not inextricably linked with all videogames, but nor is it a bad thing. Designers, as much as they can judge how easy or difficult individual players will find a videogame, make a conscious decision whether their game will be considered challenging (as with Dark Souls) or accessible (as with Animal Crossing). This decision in turn colours the narrative of the videogame, in the same way that the use of long or short sentences, or obscure of common words, can alter the style and tone of a book. For example, the impression a difficult game may give is that life is full of challenges, but through challenge emerges reward, satisfaction, and achievement. That Dark Souls is so challenging adds a further dimension to its ambient narrative about a dying world in which just surviving is an achievement within itself. Bright and cheerful Animal Crossing on the other hand, which has no explicit goals or end-game, is all about social interaction, the sense of community, and creating, or helping to create, a visually-pleasing and harmonious house and town. Making this game challenging, having the player-character able to die or fail would not be appropriate.

I would also like to point out that, just as some games are challenging and others are not, some books are challenging. Take Finnegans Wake as an example. While you can physically flick through all the pages in any order you like (in contrast to a challenging videogame which may halt progress completely if you cannot overcome a specific barrier) following Joyce's idiolectic neologistic novel is considered one of the greatest literary challenges there is. While physically following the labyrinthine narrative of Mark Z. Danielewski's House of Leaves is a spatial challenge, as the reader is asked to flick back and forth between text, footnotes and appendices, or to rotate the book as words spiral around the page. These and, to a lesser extent, many other literary works, are challenging books, in the way that Harry Potter novels are not. Again, films can be challenging, such as the puzzle-boxes Christopher Nolan directs, or the philosophically searching works such as The Seventh Seal and Paris, Texas, in the way that, for example, The Naked Gun trilogy is not.

The final 'problem' with videogames as a narrative medium are the pre- and mis-conceptions which surround it. This is due in large part to its relative youth as a story-telling device. It is true that the largest demographic for videogames is currently a male ages 18-34 audience. Older people are generally resistant to learning videogames, or have just not been exposed to them. Nintendo, particularly with the DS and DS XL series has made some great progress with getting videogames into the hands of older and female players, and not just with casual or gender-stereotyped videogames, but with story-driven titles such as Another Code, the Professor Layton series, and the Ace Attorney series among others. Gradually, the balance is shifting to encompass a wider audience, particularly as the people who grew up playing videogames start to make them, and there are now a few more high profile women in the videogames-industry, such as Amy Hennig (lead script-writer and director on the Uncharted series), but for now, males age 18-34 is the dominant demographic, and the most popular videogames reflect this.

|

| This is what males age 18-34 like |

Because games aimed at this market, such as Call of Duty, Gears of War, Halo, Medal of Honor, and Battlefield, dominate the charts, there is a misconception that most, if not all, videogames are violent. Violence is a tool used extensively by many mediums, particularly novels and films, but it is disproportionately prevalent in videogames. The reason for this, aside from the apparent appetite in the target demographic for simulations of war and murder, is that, in order to be compelling, a narrative needs some sort of conflict, and violence is an easy way to create conflict with a clear win/lose state:

Conflict - this soldier is trying to kill you. Win state - you kill him. Lose state - he kills you.

Even games which don't feature blood and guns can often be violent. The family-friendly Super Mario games for example feature no other form of conflict resolution than stomping on antagonists' heads. Even cartoonish Angry Birds is full of cartoonish violence.

Yet there are vast swathes of games which are completely, or almost completely, non-violent. Almost all simulation games for a start: racing games, plane simulations, most sports, simulations of various jobs (eg. farming, truck-driving, videogame developing), then stuff like the Sims, SimCity, Spore, Civilization games (depending on player choices), Dear Esther, Minecraft, Animal Crossing, Portal and other puzzle videogames, and many Adventure videogames. While prevalent then, violence in videogames is not universal, as is sometimes believed to be the case. (And some of these games are even pretty popular: Minecraft recently overtook Modern Warfare 3 as the most played game on Xbox Live.)

|

| Animal Crossing is a nice game for nice people |

Primarily, aside from their unique attribute of interactivity, of their level of responsiveness to their players, which I'll come to in a minute, they can combine at will elements of almost all other mediums.

Firstly, videogames often borrow heavily from film. They are, unlike books or raido-plays, a visual medium. So they can use filmic techniques such as match scenes, quick cuts, visual cues, music soundtracks and ambient noises to create atmosphere etc. Anything a film can do, a videogame could theoretically do too, and videogames frequently ape films often to great effect, sometimes to lesser effect. Some videogames may be criticised for example for sacrificing interactivity to lengthy expositional cutscenes (eg. Hideo Kojima videogames). Other videogames, such as the earlier Silent Hill and Resident Evil games have been lauded for their use of mise-en-scene and carefully considered framing, creating the impression of acting out a horror film.

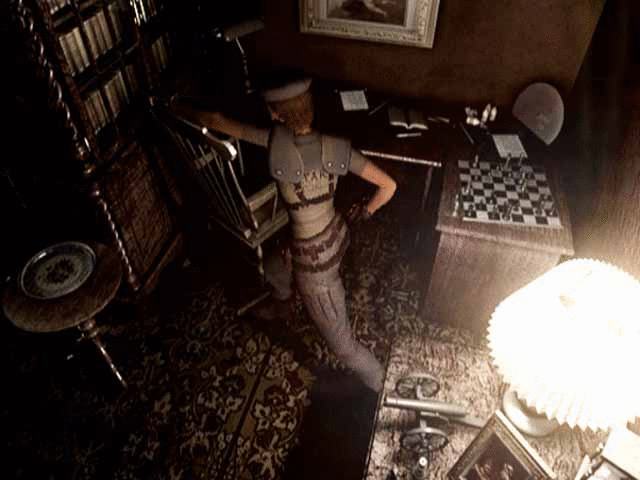

|

| Resident Evil used fixed camera angles and carefully considered lighting to create a horror-film ambiance in its creepy mansion setting. |

Bioshock is a similar example of how videogames can use audio, something equivalent to a radio-play, to expand the fiction. Through the contrivance that everyone in the world of Rapture recorded an audio diary and then left the cassettes scattered carelessly around, the player could listed to the thoughts and experiences of absent characters without breaking the first-person perspective of the protagonist. Although contrived in this game, the idea that information can come in multiple forms: as witnessed events, flashbacks, text, music, and spoken word, is closer to real life, but is not possible in many other mediums. Can you imagine a film which paused the action for several minutes while the whole audience read through a document several pages long? Or a book which asked you to stop reading at certain points and watch a short video showing certain events? Only videogames have the ability to mix these forms coherently, whether or not this ability is always implemented well.

|

| Rapture citizen: "guess I'll just record my most intimate personal secrets on this tape player and then leave it lying around in a public area." |

The second main reason videogames are a strong tool for conveying narratives is their interactivity. If you haven't already, I highly recommend you play Passage, which I linked to earlier in this post. That narrative would not work so elegantly in any other medium other than a videogame. It is a game about a life. You can choose how your avatar lives that life. If you hold right, you can walk the straight path through life, meet a wife, walk through life with her, growing old, and then she dies, and then you die. Or you can choose to avoid the girl and go through life alone. Or you can choose to not move, to stay in one place and let time pass you by. Or you can choose to explore, to go up or down and find chests containing gold coins. However, if you choose to have a wife, some of the chests may become inaccessible, as the opening to them are wide enough for only one person. You can interpret these metaphors however you like, but they could not have been presented with such clarity in a short story or a film, nor could you, as a player, have felt such agency or involvement in any other medium.

To expand upon this point, interactivity increases involvement and, often, empathy. You might get scared watching horror films, you might become infuriated with the protagonist who never turns round when the monster is behind them, but if you're playing a horror videogame, you become the protagonist, you are in control of when they turn round, whether they fight the monster or try to flee. Any threat requires your immediate action, not your passive observance. Similarly, if you've spent 40 hours building up a character from a lowly villager to a mighty warrior, specialising in weapons and skills of your choosing, you feel a level of involvement with that character you are unlikely to feel with a character in a film or television series (although I've heard a lot of people feel they can vicariously live through the characters of the series Friends).

This emotional involvement can be very powerful, and I've heard of people crying at Final Fantasy games before, particularly at that one moment in Final Fantasy VII (whose impact was much blunted for me by the fact that I knew it was coming and wasn't much enjoying the game anyway). The moment to which I'm referring of course being the unexpected death of one of the main characters, who the player as nurtured and seen develop throughout the previous 20 hours, at the hands of the story's main villain.

|

| It may not look much now, but in 1997 this scene brought some people to tears. |

Beyond empathy, interactivity also provides alternative and emergent narratives. The Silent Hill games, for example, though telling linear stories, have always featured alternative endings based on player behaviour. In Silent Hill 2, there is a female character called Maria who moves more slowly than the player's running speed. If the player chooses to wait for her and keep her in sight and to look out for her when there are monsters around, the game will end with the protagonist beginning a relationship with Maria. However, if the player chooses to move through the game as quickly as possible, leaving her behind, there will be a different, equally valid conclusion.

This is similar to the alternate ending feature you sometimes get with DVDs, but other games weave diverging narratives throughout their experience. In Dragon Age: Origins you can choose different reactions during conversations and this will affect how the characters present respond to you in later conversations. Many roleplaying games employ similar mechanics, while strategy/simulation games often present even more choices. Will Wright's SimCity and Sid Meier's Civilization series, for example, in each of their videogames offer all players the same starting tools, but no two play-sessions are alike, and all players will leave with different stories to tell, and yet you could not novelise either of these games.

Some people would argue that interactivity, the handing over of agency to the player, takes away the control of the author and makes it impossible for videogames to tell proper stories and, furthermore, impossible for videogames to be classed as art. This I would say emphatically is not the case. Any videogame world exists within what is known as a possibility space, a term which is more-or-less self-explanatory. A gameworld is a space in which some things are possible, and some things are not. Things which one game allows may not be allowed in another game, following conscious design decisions and an editing process, and this can have a profound effect on the narrative.

Take, for example, a hypothetical game in which you play as a law enforcer in a fictional city. The game might allow you to kill innocent civilians, or it might prevent your gun from firing when pointed at an innocent person. If the player is able to kill a civilian, this might play into part of a narrative about police brutality or negligence, which could further be coloured by whether killing a civilian has no consequences (the resulting narrative making a comment on accountability and who polices the police) or there is some punishment for doing so (this playing into a narrative about how people are free to make their own choices, but choices have repercussions). Alternatively, if the game prevented you from ever harming a civilian, this would enhance the portrayal of the protagonist as a heroic and morally righteous person who only harms bad guys.

Through design choices such as these, if considered carefully, the designers allow the player to discover a narrative for themselves within the intentions of the author. Thus, both authorial control and player agency are served and a narrative is conveyed.

The other benefit of interactivity, which perhaps I should have mentioned earlier when I was talking about letting players read further exposition as and when they wanted, is that players can choose, to an extent, how long to linger in certain places, or in what depth to study them. For example, in role-playing videogames especially, some players like only to follow the main story-line and then reach the conclusion, while others like to take their time and experience all the side stories/quests the gameworld has to offer. This is an option not present in films, books, or television series. Secondly it allows for virtual tourism of real, historical, and fantastical places.

The Assassin's Creed games, with their painstaking recreation of historical cities, are strong examples of this. You can read about 15th Century Florence, you can watch documentaries, or historical dramas set there, you can even visit the modern day city and imagine what it must have been like, but only Assassin's Creed II let's you see a facsimile of what it must actually have been like to explore the city's backstreets, to look out from the rooftops, to hear the ambient sounds and see the people going about their daily lives. And how much more captivating to experience it that way, than to look at illustrations in a dusty textbook?

|

| Renaissance Florence lives again! |

My final reason why videogames are such a strong medium is that they are not limited by time constraints in the way that just about any medium apart from literature is. Any film over three hours, however enjoyable, is an endurance test. People will not go to the cinema in droves to sit for 200+ minutes in one go. Same with stage-plays, and radio-plays. Television and radio serials fare slightly better in that these can run for hundreds of episodes (eg. Doctor Who, the X-Files, the Archers) but these are limited by needing to have segments of uniform length: usually 30-, 45-, or 60-minute blocks. This leads to episodes which begin to follow familiar formulas and beats in the plot, and leaves little room for experimentation.

Only literature and videogames escape the formal length constraints which affect other mediums. Literature can, of course, be pretty much any length from around 6 words to well, theoretically any length, but in practice, not much more than 1,000,000 words. This can be broken down into different forms roughly as follows: 1-500 words - flash fiction, 500-20,000 words - short story, 20,000-40,000 words - novella, 40,000 words+ - novel (and possibly 200,000 words+ - epic novel). Similarly, videogames can be anything from the 5-minute long Passage, mentioned above, to 100 hours+ epics such as the Elder Scrolls games and World of Warcraft.

And that's pretty much my argument for why videogames are the strongest medium for conveying narratives we have yet conceived. To recap they (1) are able to handpick the best elements of other mediums for their own purposes, (2) are interactive, creating a range of potential alternative yet interrelated narratives which can occur within a single possibility space, and (3) they are not constrained by requirements to adhere to certain minimum or maximum lengths, expanding the range and breadth of stories they can tell.

As a young medium they may not yet always live up to this potential, and they still have some stereotypes and misconceptions to shake off, but I am optimistic that one day the great power of narratives told through videogames will be more widely recognised.

*This is a fairly arbitrary cut-off point, but I'm basing it on the assumption that many of the games from the early '90s, particularly those on the NES (1986), Megadrive (1988) and SNES (1990), were influenced by, or even ported from, coin-hungry arcade cabinets which sought to keep play-sessions short and leave players hungry to improve their performance. I would say the advent of the Nintendo 64 in 1996 and particularly it's launch game, Super Mario 64, began a trend towards more accessible games, since the 3D world was more forgiving than its 2D forebears were just staying alive was a challenge.